Everyone has heard “House of the Rising Sun.” It’s a world-wide radio staple. Most assume that it’s really about a brothel in New Orleans. It may be. There definitely were hotels there named "Rising Sun” and perhaps some were bordellos. But folksinger Dave Van Ronk once saw a postcard of a New Orleans women’s prison with a rising sun design on its door and he believed that was the basis for the song. Another theory is that it’s about a hospital, specifically a T.B. (tuberculosis) ward. There is one old building in New Orleans that once was a T.B. ward and it has a rising sun in relief on the lintel above the front doors. The rising sun was a popular and widespread design motif expressed in 19th century American architecture and it evidently found its way onto a variety of places to avoid.

Some versions of the song don’t refer to New Orleans at all. One collected in the far west looks to Brooklyn, New York as the place to avoid, and another collected in Tennessee warns against the evils of Baxter Springs, a cow town in Missouri that had its heyday in the mid 1800’s as a place where cowboys came to play.

There is a girl in Baxter Springs, they call her the Rising

Sun;

She has broken the heart of nine, love, boys, and this poor heart

is one.

In the early 1800’s economic hardships led many Appalachian families to migrate further west. Many eventually settled in the Ozark Mountains of Arkansas and Missouri. Folklorists have collected multiple versions of “Rising Sun” from a variety of Ozark locations but none refer to Baxter Springs. Perhaps the Tennessee version was a lament about the sad but necessary migration west?

As we see in the Baxter Springs tale the name “Rising Sun” doesn’t always apply to the business establishment. In another version discovered by musician and folklorist John Cohen in the late 1950’s called “Sport in New Orleans,” singer Dillard Chandler of Sodom, North Carolina also referred to the female trouble maker ('sport' was a southern euphemism for 'prostitute') as “Rising Sun.”

Most people assume that the story is always told from the male perspective. Not always true. In some versions the protagonist voice is female. In the earliest written version of the song found in the National Archives, a tune called “Rising Sun Dance Hall,” the hall is the “ruin of many a poor girl, Great God and I for one.” In this case the “young and foolish poor girl let a rounder lead me astray.”

It’s also commonly thought that the song came from the African-American musical tradition. This is based primarily upon the assumption that the song originated in New Orleans, a major port in the slave trade with a large African-American population, and the city that gave us jazz. The evidence as collected by Alan Lomax and other ethnomusicologists and folklorists disagrees.

In all of his years of music collecting Lomax only found

versions of the song in southern white Anglo communities. African American folk

singer Josh White (b. 1914) seems to confirm this in his autobiographical “The

Josh White Songbook.” As a youngster in North

Carolina he heard the tune performed by a “white

hillbilly singer.” The hillbilly singer may have been Homer “Bill”

Callahan or Clarence “Tom” Ashley. Both toured extensively throughout the south

at that time, and both later recorded versions of it.

Callahan was born in 1912 in North Carolina and learned the song from “a neighbor across the mountains.” According to Callahan it was about a 'notch house' -- a gambling and prostitution house. Callahan became a professional musician as a teen and performed with his brother all over the south. In 1927 he recorded “Rounder’s Luck,” his version of “House of the Rising Sun.”

Ashley was born in 1895 in a town on the border of Tennessee and Virginia. He learned “Rising Sun Blues” at a young age from his maternal grandparents. In 1911 he joined Doc Hauer’s Traveling Medicine Show and toured for 30 years, performing in towns, villages, mining and timber camps, anywhere that a crowd could gather who would be interested in being entertained and in purchasing medicinal elixirs. Traveling medicine shows were the primary form of professional entertainment in the rural south and the musicians who performed with them were on a never-ending tour with a vast audience. In 1933 Ashley recorded “Rising Sun Blues” for the Vocalion label. His recording has a unique verse that expresses a very bleak opinion about the honesty of women. "Now boys, don’t believe what a young girl will tell you, let her eyes be blue or brown. Unless she's on some scaffold high, sayin’ “Boys, I can’t come down.”

The only time a woman can be trusted to tell the truth is when she is about to meet her maker!

In 1953 Alan Lomax went to England to record balladeers. He was looking for the roots of some of the traditional tunes that he had recorded throughout America. He noted that “House of the Rising Sun” shared similar subject matter and meter with a few British ballads, notably “Lord Barnard & Little Musgrave” (aka “Matty Groves”) which dates from the 16th century. In England Lomax met Harry Cox, a laborer and balladeer who was born in 1885 and had an extensive repertoire of songs that he learned from his father and from a lifetime of pub singing. When Cox offered to sing Lomax an old “dirty song” Lomax turned on his tape recorder to capture:

If you go to Lowestoft and ask for the Rising

Sun,

There you’ll find two old whores, and my old woman’s one.

This version is clearly about a brothel, sung from the man’s perspective. Lowestoft is on the eastern seaboard and is sometimes associated in a promotional manner with the rising sun. It once had a pub called the 'Rising Sun' but no evidence of a brothel of that name. How the tune arrived in Lowestoft is unknown but somehow between England and the American south it transitioned from its “bawdy song” origins into a “cautionary tale.” Brought to the Appalachians by English, Scots & Irish immigrants, it found a home and continued appreciation in small rural communities with a message that warns about the effects and dangers of big city life upon small town men and women, a song about the moral dangers of leaving home; certainly a widespread and deeply held sentiment.

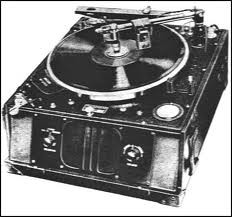

Lomax had first heard the tune in 1937 when his Library of Congress expedition took him through the Cumberland Gap into Appalachia. He recorded three separate renditions of the song on his Presto disc making machine and the most influential recording was made in Middlesboro, Kentucky by sixteen year old Georgia Turner (b. 1921). A descendent of English, Scots, and Irish settlers, Georgia grew up without electricity (no records or radio) but most likely attending traveling medicine shows where she may have heard Tom Ashley or Roy Acuff perform it; but this is conjecture. Perhaps she learned it from her ancestors who brought it with them from the British Isles.Whomever she heard it from, she seems to have made it her own. Turner’s is a bluesy rendition; using a blues scale in a major key that includes vocal scoops and slides, all hallmarks of American blues style vocals. She tells the tale from the female perspective:

My mother she’s a tailor, she’d sew those new

blue jeans

My sweetheart he’s a drunkard, Lord, Lord, drinks down in New Orleans.

Turner’s melody is the version that Lomax transcribed for sheet music publication. He published the sheet music (the lyrics were a composite from all three field recordings) in his 1941 book “Our Singing Country,” and he graciously listed Turner as ‘arranger’ so she could collect some royalties. Back in New York City his enthusiasm for the song was shared with Pete Seeger, Woody Guthrie, Josh White and Leadbelly. Seeger told journalist Ted Anthony that Lomax “purposefully tried to infect us with the music that he collected.” In this case he succeeded as Seeger’s Almanac Singers, Leadbelly and Josh White all recorded versions in the 1940’s, and by the early 1950’s “House of the Rising Sun” was a folk music standard being performed by everyone who called themselves a folk musician. Josh White’s version is especially interesting: He is the first to record it in a minor key giving it a much darker feel, and as the track fades out you can hear a quiet arpeggio. Those two additions became central features of the most well-known version of the song that was to be recorded almost twenty years later.

According to a number of his musical peers when Bob Dylan

first showed up in New York

in 1961 he copied his idol and performed the published Lomax version of “Rising

Sun” just as Woody Guthrie did until he heard Dave Van Ronk. Dylan disagrees. He

writes that Van Ronk “seemed ancient, battle-tested. Every night I sat at

the foot of a time-worn monument…I’d never heard that song [Rising Sun] before,

but I heard it every night because Van Ronk would do it. I thought he was

really onto something with that song. So I recorded it.” Dave Van Ronk

came from a jazz background to folk music and to this song in the 1950’s. He

played “House of the Rising Son” using Lomax’s lyric text but he altered the

chords and used a jazz-like descending half-step progression.

Van Ronk writes: “Bobby picked up the chord changes from me…it really altered the song considerably…He asked me if I would mind if he recorded my version. And I had plans to record it so I said ‘Gee Bob, I’d rather you didn’t because I’m going to record it myself soon.’ And Bobby said, ‘Uh-oh.’ He had already recorded it.” Van Ronk claimed to be only slightly perturbed at the time. Eventually though he stopped performing the song because once Dylan’s album came out everyone thought it was Dylan’s song. Writes Van Ronk: “Now that was very annoying!”

In 1964, the Animals were a young English blues band that was the opening act of a Chuck Berry & Jerry Lee Lewis concert tour of England. They were primarily playing covers of blues standards but were looking for something new to play on tour; something to encore with. Singer Eric Burdon told Ted Anthony, “you can’t out-rock Chuck Berry” so the band wanted something that was distinctive and powerful but not rock ‘n roll. How they came upon “House of the Rising Son” is unclear. Burdon says he was familiar with Josh White’s version. Drummer John Steel says that it was strictly Dylan’s version that provided inspiration; he insists that none of the members were familiar with the song until they heard Dylan’s album. They arranged it and rehearsed it collectively and then began performing it on stage. The audience reaction was immediate and ecstatic. In mid-tour they went into a studio and in ten minutes recorded the four minute single that most of the civilized world is now familiar with. Both their organist Alan Price and their producer Mickie Most didn’t want to record it; it was too long and it was about prostitution! But the producer gave in only because it was copy-right free and therefore wouldn’t cost him anything. Guitarist Hilton Valentine told Anthony “we took the chord sequence from the Dylan version and used arpeggios instead of strumming.” The guitarist’s seven-note intro arpeggio provides the building blocks of this version. Burdon’s vocals and Alan Prices’ organ build into a minor key blues crescendo. Within a few months it was a radio hit. The Animals became 60’s superstars but only one member profited from the sales of their hit. Alan Price was given arranger’s credit on the record. He’s received full publishing royalties ever since. The other band members receive nothing. Given Price’s original lack of enthusiasm for the tune his band mate’s animosity and sense of betrayal runs deep.

But in music as in life what goes around sometimes comes around, and in a filmed interview Van Ronk tells Martin Scorcese: “Later on, when Eric Burdon and the Animals picked the song up from Bobby and recorded it, Bobby told me that he had to drop the song because everyone was accusing him of ripping it off of Eric Burdon.” Then Van Ronk laughs. And in an Animals bio Steel and Burdon both say that Dylan told them that when he heard the Animals version on his car radio he had to stop driving to listen. It was a game-changer for him. That’s what he wanted his songs to sound like: Electric.

So from the pubs of England to American medicine shows to the ears of Georgia Turner; from Turner to Lomax’s Presto disc making machine to urban folk singers; from Van Ronk to Dylan and Dylan to the Animals (and back at Dylan!) From England to America and back to England again, and then out across the globe. That’s how an old folk song came to be recorded in every language that has a commercial music market and ends up firmly implanted in the musical consciousness of the world.

Sources: “Chronicles Volume 1” by Bob Dylan (Simon & Schuster 2004), “Mayor of McDougal Street: A Memoir” by Dave Van Ronk (Da Capo Press 2005), “Josh White: Society Blues” by Elijah Wald (UMass Press 2000), “Chasing the Rising Sun: Journey of an American Song” by Ted Anthony (Simon & Schuster 2007). Ted Anthony’s obsession with “House of the Rising Sun” has produced the definitive book about the song. Anthony is a journalist for the Associated Press. In his spare time he bought every recording he could find of the song and traveled the country and world in search of answers to his questions about it.