This week 33 miners were killed in a subterreanean explosion in China. Nothing new here. Mining is still one of the world’s most dangerous occupations and Peggy Seeger’s song “The Ballad of Springhill Mine” is as relevant today as when it was inspired fifty-eight years ago this past October. That tragedy was brought into everyone's living room when it became the first ever world-wide broadcast of a rescue mission. That event in 1958 riveted viewers all across the globe.

In the town of Springhill, Nova Scotia

Down in the dark of the Cumberland

Mine

There’s blood on the coal and the miners lie

In the roads that never see sun nor sky.

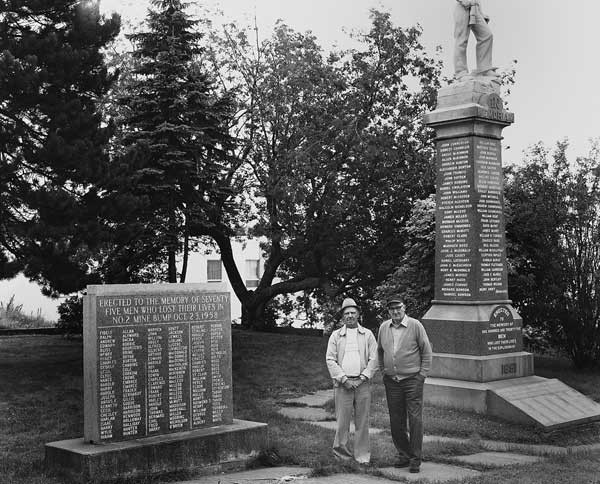

Springhill, Nova Scotia is built on coal. By the 1870’s the deepest coal mine in the world channeled underneath the town and the first coal miner’s union in North America was founded there in 1879. Of this union historian Ian McKay wrote: “They were giants….when they marched, the region shook.” But being giants with the rights of collective bargaining didn’t prevent injury and death: Between 1876 and 1971 the mines in Springhill claimed 668 lives, most in individual accidents. There are monuments there with all the names.

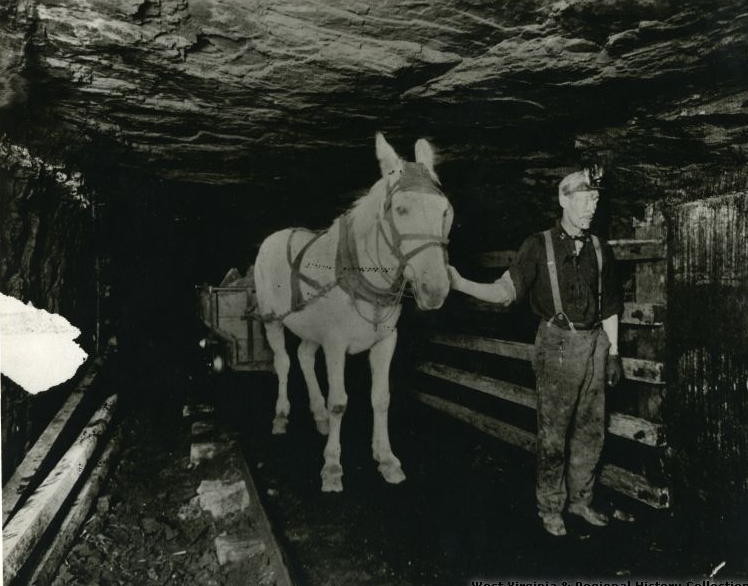

But there were also major ‘incidents’: In 1891 accumulated coal dust burst into a fireball. The men and boys and pit ponies (the short, strong blind horses that pulled the coal cars) that were not initially burned to death were eventually overcome by gas. 125 miners gone. In 1956 a coal car derailed in a shaft. Several cars broke loose and rolled backwards hitting a power line causing an arc that ignited the coal dust 5,500 feet below the surface. 39 killed but 88 rescued.

Often the earth will tremble and roll

When the earth is restless, miners die

Bone and blood is the price of coal.

On October 23, 1958 the earth shook; and not due to marching miners. An underground earthquake - a “bump” in miner’s parlance - took the lives of 74 men. The race to rescue trapped survivors became the first television ‘event’, a media sensation, as the Canadian Broadcasting Company broadcast the rescue efforts live from Springhill. It was real Reality TV with the hope, frustration, anger, joy and grief of a small Nova Scotia town being beamed around the world. The 74 dead miners soon took a back seat to the efforts and eventual rescue of two groups of 19 trapped men who were discovered and brought up after 9 days from 13,000 feet underground.

Soon after the successful rescue researchers began a series of interviews with the men. Their goal was to gain insight into the development of leadership and social structure within the “community” of trapped miners. Their research had little if nothing to do with mining: This was the Cold War era. Everyone was anticipating a nuclear event that would result in communities of bomb shelter survivors. What better way to develop an understanding of the social dynamics of desperate bomb shelter inhabitants than to study trapped miners?

Three days past and the lamps gave out

Our foreman rose on his elbow and said

We’re out of light and water and bread

So we’ll live on song and hope instead.

The research identified two periods of time when activities of the trapped men were led by two separate types of individuals. The first phase was called the “escape period.” During this time, in the days immediately following the mine’s collapse, leadership was provided by men who were good with tools and were confident and energized about using their tools to get out. Their enthusiasm, confidence, and ideas made them de facto leaders. The second phase was called the “survival period”: After the “escape” leader’s efforts to exit the mine failed they eventually lost their zeal and became despondent. Other men however stepped up. These were men “who possessed endurance, and the intellectual and spiritual resources” to provide solace and hope. They become de facto leaders until the rescue was completed.

Listen through the rubble for a rescue team

Six hundred feet of coal and slag

Hope imprisoned in a three foot seam

But subsequent research also showed that solace and hope were not enough to prevent the trapped men from turning on each other. It revealed that the camaraderie, team work and collective heroism reported by the mining company, the media, and the public statements of the miners themselves were largely fiction. Underground the horror and inescapable presence and stench of the dead were a source of great anxiety and stress for the survivors. The cries, moans and pleas of the trapped, injured and dying friends, relatives and co-workers especially took its toll. “Survivor’s guilt” surfaced before the trapped men did. Their anxieties developed into distrust for each other and for the motivations of others. Men formed alliances and cliques rooted in mistrust and suspicion. Interviews with the rescued men a decade later showed that the trauma of their ordeal had a lasting, souring effect on their relationships with co-workers and neighbors long afterwards. Years later the survivors were still questioning the motivations of their underground companions. They just couldn't shake off the darkness of the mine.

After the 1958 “bump” the mine operator, Dominion Steel & Coal, closed its operation in Springhill. Other local mining companies continued however into the early 1970’s. Today, beneath the monument to the dead, Springhill’s mine shafts remain some of the deepest in the world. They are filled with water, are owned by the Canadian government, and are used as a source of geothermal heat.

Source: There have been quite a few books written about the Springhill disaster. The most recent and most thoroughly researched is Melissa Fay Greene's "Last Man Out" (2003, Harcourt Publishing). She discovered the audio tapes of the miners who were interviewed by the government funded researchers and used them to recount the conditions and activities within the mine and afterward.

There's a secondary storyline that Greene writes about that is sad, funny and poignant. It illustrates the political and social climate of the times: North Carolina politicians were attempting to open up their outer coastline to tourism. They wanted to be a tourist destination like Florida. After seeing a photo of the 19 coal-covered survivors, as a public relations/advertising move they invited them all down for free accommodation at a new coastal resort. What they didn't realize was that underneath the coat of black coal dust on one miner was black skin. Who would have thought that there was anyone other than white people in Nova Scotia?! How the racist governor dealt with this threat to segregation while upholding the invitation to the entire group required some shifty maneuvering.

Here is a Canadian website that features an archive of historical photos relating to the 1956 & 1958 Springhill disasters:http://gov.ns.ca/nsarm/virtual/meninmines/archives.asp?ID=828&Language=English